By Richard Martin & Daren Sweeney, S&P Global

This is the third of a five-part series exploring oversupply in the power sector and the factors driving a glut of natural gas-fired power plants.

When Dominion Energy Virginia decided in 2012 to convert two units of its coal-fired Bremo Bluff power station to burn natural gas, it pledged that the conversion at the Fluvanna County plant would save customers $32 million compared to the cost of building new gas-fired generation and $155 million compared to continued operation on coal.

Those benefits never materialized. Instead, in December 2018, four years after the conversion was completed, the company known legally as Virginia Electric and Power Co. placed the Bremo units in “cold reserve” along with several other generating units, idling more than 1,200 MW in total, nearly three-quarters the size of Virginia’s largest power plant, the North Anna Nuclear Generating Station. And earlier this year, Dominion Energy Inc. executives announced they would permanently shut down the idled Bremo Bluff units.

But despite a dramatic fall in power prices and its decision to mothball a significant portion of its generating fleet, Dominion continues to add more natural gas generation capacity.An examination of State Corporation Commission, or SCC, records; Dominion’s past integrated resource plans, or IRPs; campaign finance documents; and independent reports, along with interviews with utility analysts and environmental advocates and statements from Dominion officials, shows that the company has consistently over-forecast electricity demand to justify building new capacity, primarily natural gas plants with dubious economics that will ultimately be paid for by ratepayers.

The utility said it plans to add at least eight new natural gas-fired plants, totaling nearly 3,700 MW, by 2033, according to its 2018 integrated resource plan,. An update to the IRP outlines three alternatives that call for adding 2,425 MW of natural gas-powered combustion turbine capacity by 2044.

That is on top of two large gas plants that recently came online: the Brunswick County Power Station, which started up in April 2016, and the Greensville Power Station, brought online in December 2018. Together, those two plants total more than 3,000 MW of new gas-fired generation capacity and cost more than $2 billion to build.

The proposals come as electricity demand in Virginia grew less than 1% from the Great Recession of 2007-2008 through 2017, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, and is projected to remain essentially flat for at least the next decade. In an era of little to no demand growth, when it is already removing plants from service long before their planned retirement dates, Dominion continues to add thousands of megawatts of new gas-fired capacity. And since it is a regulated monopoly, the company continues to pass the costs of those plants along to its customers.

“Dominion is on a massive natural-gas building spree, having added five plants in the last 10 years,” said Will Cleveland, an attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center who has represented the group in proceedings before the SCC involving Dominion for several years. “Their forecasts have consistently and inaccurately over-predicted load. And when the commissioners ask ‘What are you doing to fix it?’ the answer is ‘Nothing.’”

Dominion Energy spokeswoman Audrey Cannon said the company is “investing in natural gas because it’s a great partner for renewables.”

Natural gas “helps fill in the gaps when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing,” Cannon said in a Nov. 1 email response to questions about the company’s resource plans. “Renewables alone don’t have the capacity to meet the peak demand of our customers. That’s why a diverse energy mix — including solar and wind as well as natural gas and zero-carbon nuclear energy — is critical to serving our customers reliably and affordably.”

Times a’changing

Now, though, the era of untrammeled building by Dominion could be coming to an end.

In December 2018, the SCC rejected Dominion Energy Virginia’s proposed IRP, finding that the company’s forecasts “have been consistently overstated, particularly in years since 2012, with high growth expectations despite generally flat actual results each year.”

Dominion’s plan failed to model $870 million in energy efficiency programs and a battery storage pilot as required by a landmark 2018 state law known as the Grid Transformation and Security Act, the commissioners said. The regulators ordered the company to “correct and refile” the IRP and not to rely on its internal load forecasts in future IRPs.

In mid-January, the SCC also rejected about 90% of Dominion Energy Virginia’s proposed grid transformation plan, filed under the new law. The overall plan was “unsupported by the evidence,” the regulators said, and too costly for customers.

Meanwhile, a growing number of state legislators and other political officials have declared that they will no longer accept campaign contributions from Dominion, which for many years was the largest corporate contributor to political campaigns in the state of Virginia. The shift was underscored by the November general election, in which Democrats took full control of the Virginia General Assembly for the first time in 26 years.

“Dominion’s stranglehold on the Virginia state legislature is slowly loosening,” Harrison Wallace, Virginia director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network Action Fund, said in a statement following the election. “Now it’s up to our leaders to put Virginia on the path to 100% clean energy.”

“Now, the times they are a-changing,” said former Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, who served several years in the General Assembly and who is now the acting director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services under President Donald Trump. “There’s a political price now to be paid on both sides of the aisle for just doing what Dominion wants. They don’t get to just say what they want and go get it. It’s a fight now. And it’s a fight with political costs.”

Cuccinelli, a Republican, has formed an unlikely alliance with left-leaning groups to fight Dominion’s power in the state, including Clean Virginia, founded by Charlottesville, Va., investor Michael Bills. Bills’ Clean Virginia has endorsed a slate of 61 candidates for the state legislature, most of them challengers to long-seated incumbents and all of whom have refused to accept money from Dominion.

“Our problem is not convincing people, it’s just educating them about the way the system is,” said Brennan Gilmore, executive director of Clean Virginia. “Once they realize Virginia is a place where a regulated monopoly can give endless amounts of money to politicians who then have to regulate it, they understand that that’s a fundamentally broken system and want to do something to fix it.”

Attorney General Mark Herring, a potential Democratic candidate for governor in 2021, has also pledged to no longer take campaign donations from state-regulated monopolies, including Dominion, based on the “lack of public trust” in government oversight that this creates. “That’s something that I think I could do to help restore the public’s trust,” Herring told the blog Blue Virginia.

The shift in pressure marks an abrupt turn of fortune for Dominion, which has long wielded considerable political power in its home state of Virginia. At the very least, it means that Dominion could face more resistance to new gas plants in the future.

Often, Dominion has used its influence to win regulatory approval for new power plants in Virginia, according to Cuccinelli. “I’ve been paying attention to this specifically since I got elected to the state Senate in 2002,” Cuccinelli said in an interview. “And sitting here talking to you more than 16 years later, I can’t name a time they didn’t basically get one of these requests granted. “If they had to go change the law to do it, they did it. Really without much trouble.”

Doubling down on gas

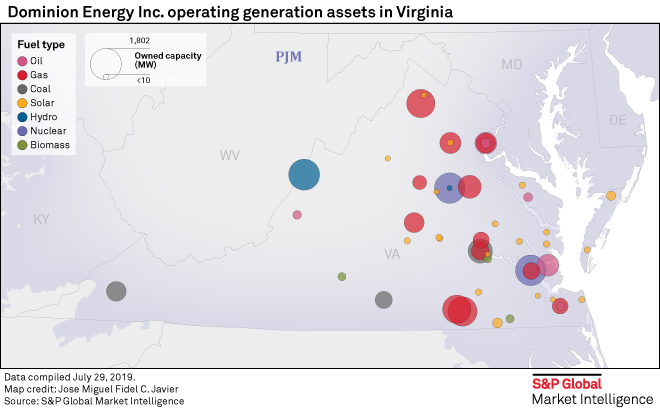

Dominion Energy’s portfolio includes 8,989 MW of operating natural gas capacity announced since 2000, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. In addition to at least 4,700 MW of new solar capacity in the next 15 years, all of the scenarios modeled in Dominion’s 2018 IRP involve the addition of eight new natural-gas-fired power plants by 2033, with a combined capacity of up to 3,664 MW.

To justify building these new plants and passing on the costs to ratepayers, Dominion has consistently produced load-growth forecasts that have proven to be overestimated — and that exceed those produced by PJM Interconnection, the grid operator whose territory includes Virginia and that has acknowledged that its own forecasts were overly optimistic for years.

In 2017, for example, PJM forecast that load growth in Dominion’s service territory would be relatively flat through 2032, reaching just over 20,000 MW. In its 2017 IRP, by contrast, Dominion said load would grow steadily, reaching nearly 25,000 MW by 2032. The difference equates to three major gas-fired plants the size of the 1,588-MW Greensville Power Station.

Justifying these aggressive forecasts, Dominion has claimed that growth in data centers in the state, which has become a major hub for online traffic, will dramatically increase electricity demand.

“Data centers are just an unbelievable growth machine for us,” former Dominion Energy Executive Vice President and CFO Mark McGettrick said on a May 2017 earnings call. At the time, Dominion said data centers made up about 18% of the company’s commercial load. In August 2017, Dominion Energy Chairman, President and CEO Thomas Farrell II said higher electricity sales to data centers and residential customers, along with increased defense spending, would support electric sales growth of at least 1% annually.

Tech companies, however, have questioned those assumptions, and they have pursued plans to purchase renewable energy for their facilities. In a September 2018 letter to the SCC, a group of data center operators, including eBay Inc. and salesforce.com inc., said the need for electricity from conventional power plants will dwindle as the data industry becomes more energy-efficient and shifts toward renewable energy. Many of the largest owners of data centers in the state, including Amazon.com Inc. and Microsoft Corp., have committed to 100% renewable energy, and access to renewable energy “is a significant factor in deciding whether to locate or expand new data centers within the Commonwealth,” the letter stated.

Nevertheless, Dominion continues to defend its forecast models, which show demand increasing into the foreseeable future.

“We find our forecasts have been much closer to the actual figures than the other models,” Dominion spokesman Rayhan Daudani said in an interview. “In the long term, the type and amount of generation resources might get realigned to meet the load, but solar along with gas-fired power stations remains the best option for our customers for reliability and cost.”

A flaw in the scheme

As Virginia’s political winds shift, Dominion continues to be one of the most profitable U.S. utilities. According to data compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence, Dominion ranks second among U.S. utilities in terms of recurring EBITDA margin, just behind NextEra Energy Inc.

Like many regulated utilities, Dominion makes money not only by selling electricity but also by building new plants. While 19 states have decoupled power generation from transmission and other utility operations, Virginia remains vertically integrated, allowing Dominion to be paid in full for new capacity, including an approved profit. For a plant that costs $1 billion to build, for example, customers could pay up to $3.5 billion over the facility’s 40-year life after financing costs and utility returns are included, according to an analysis by Tom Hadwin, a former utility executive who now acts as a pro bono consultant to the Southern Environmental Law Center and other organizations.

“This amount will be recovered from ratepayers regardless of how much the unit runs and whether it does so profitably,” said Hadwin. “This is a major flaw in Virginia’s regulatory scheme and families and businesses will pay a heavy price for it,” he added. “Dominion is proposing thousands of MW of additional generation beyond what its demand requires in order to cash in on this.”

In the case of the Greensville Power Station, Dominion was cleared to make an initial 9.6% return, eventually lowered to 9.2%, under a rate adjustment clause that added about 75 cents a month to a typical customer’s bill — despite the rate freeze that was enacted in 2015.

The Greensville project generated fierce opposition from environmental and ratepayer groups, which argued that the utility had not considered alternatives such as solar power and energy efficiency measures.

The SCC, however, not only found that the company “undertook serious and credible efforts” to investigate non-fossil-fuel options, but also granted the rate adjustment clause to boost Dominion’s earnings. Such adjustment clauses have been attached to each of the large natural gas plants constructed or developed by Dominion in recent years.

In addition, ratepayers across PJM’s territory pay for those plants to be online and available for dispatch. That revenue also flows to Dominion, which uses it to offset customers’ bills through various bill adjustments.

“The revenue from the energy sales to PJM is a credit to our customers in the fuel factor,” Dominion spokesperson Audrey Cannon said in an email. “In other words, all revenue we receive from selling energy into PJM is passed on dollar-for-dollar to our customers each year.”

The revenue the company receives from its capacity sales is “netted out against the cost” of capacity purchases, Cannon said, and the net revenue, whether positive or negative, is passed on to customers through base rates.

PJM does not make capacity payments to individual generators public, but S&P Global Market Intelligence estimates those payments based on information published by PJM, including the resource listing (i.e., available generators), peak credits (adjustments to generator capacity to reflect peak summer availability) and cleared prices. Assuming that all Dominion resources cleared the 2018 auction, S&P Global Market Intelligence estimates that its 14 gas plants, totaling 9,700 MW of summer capacity, received $381.6 million from the capacity market. That would represent about 33.2% of the total revenues those plants received by selling electricity.

Recent pushback at the SCC and in the legislature indicates that the interests of customers, along with environmental considerations, are starting to carry more weight in Virginia. After Democrats gained control of both houses of the Virginia legislature, a group known as the Virginia Energy Reform Coalition said it is “paramount” for newly elected leaders to work on “replacing the current monopoly structure that electric utilities have abused for too long.”Still winning

Still, Dominion continues to win its share of battles in Richmond.

In late June, the SCC approved Dominion’s revised long-term resource plan but raised concerns that it “may significantly understate the costs facing Dominion’s customers.”

Under the approved plan, an average residential customer will pay an additional $29.37 on their monthly bill by 2023, the regulators said. That is a 26% increase from January 2019.

The IRP calls for Dominion to build eight gas peaker units, totaling 3,644 MW of new gas generation capacity. Those plants are slated to come online between 2022 and 2033, meaning they will still be producing power well past midcentury — or they will be idled earlier, just like the plants Dominion shut off in 2018.

In any case, customers will be still be paying for them.