This article was produced in partnership with the ProPublica Local Reporting Network. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter.

This article was produced in partnership with the ProPublica Local Reporting Network. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter.

When Democrats campaigned for the Virginia legislature last year, they took aim at the state’s largest power broker: Dominion Energy.

The electric utility’s clout was legendary in the state Capitol, where it doled out millions in campaign contributions and employed an army of lobbyists who helped write energy policy for decades. The result was soaring electricity bills and an energy grid heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

Democrats vowed to change that. After winning total control at the state Capitol for the first time in a generation, lawmakers unveiled the Clean Economy Act. They said it would phase out carbon-based energy and lower consumers’ power bills.

In a stark display of role reversal, one of Dominion’s top lobbyists watched from the back of the room as Democratic lawmakers stood alongside environmentalists and clean energy backers to introduce the legislation at a press conference.

But over the next 11 weeks, Dominion fought back and ended up as a winner in a bill intended to diminish its influence. By doubling the size of its lobbying corps and tapping its long-standing relationships with legislative leaders and Gov. Ralph Northam, the utility secured in the Clean Economy Act the right to build its top priority: a massive offshore wind farm set to be the most expensive utility project in Virginia history.

State regulators estimate a typical residential customer will pay nearly $70 more per month for the same amount of electricity by the end of the decade. About 40% of that increase is tied to the new law.

At the behest of Dominion, records show, a senior Northam administration official made last-minute changes to the legislation that increased the wind project’s price tag by an estimated $2.5 billion. The tweaks meant more money for Dominion, because state law guarantees utilities roughly 10% profit on construction projects. Neither the environmental representatives who helped craft the bill nor the state senator who sponsored it said they were aware of the changes until after the legislature passed it.

What happened in those 11 weeks — detailed in emails, internal documents and dozens of interviews conducted by The Richmond Times-Dispatch and ProPublica — offers an inside look at how Dominion wields political influence in Richmond, even as growing ranks of lawmakers denounce its name and refuse its money.

Dominion defended its role in the process, saying that the legislation directly affected its business.

“If the lights go out, people call us. So the No. 1 thing we always bring in any discussion of energy bills is we’re very aware we’ve got responsibility for this — keeping the lights on,” said Bill Murray, Dominion’s head lobbyist. “And that informs sort of everything else that we do.”

He said the utility pressed for the changes to the legislation to lock in the cost of the wind project. That helps offset the risks of building offshore wind, which is more expensive than other forms of energy. The company says it can’t meet the state’s new renewable energy goals without using offshore wind.

Today, Northam and Democratic lawmakers champion the Clean Economy Act as landmark legislation that places Virginia, long among the worst states on clean energy, at the forefront of the fight against climate change. It will also promote construction of solar energy and mandate utilities generate electricity without fossil fuels by 2050.

Nevertheless, if wind costs escalate or the offshore project doesn’t produce the energy expected, Dominion’s customers will still be on the hook.

“There’s no reason that we have to make these policy decisions that say that this regulated monopoly must profit off of all of these other projects,” said Del. Sam Rasoul, a Democrat from the mountain city of Roanoke, who unsuccessfully sought to curb costs in the Clean Economy Act. “I feel as though Dominion is still solidly in control of the legislature.”

Monopoly Rule, Big Bills

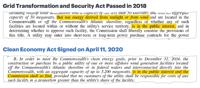

Like most public utilities, Dominion has a monopoly on its territory, providing power to two-thirds of customers in Virginia and a small slice of North Carolina. In exchange, the company is required to convince a board of independent state regulators, the State Corporation Commission, that it isn’t overcharging customers. But over the years, Dominion has pushed for and won legislation that undercuts regulators’ authority.

In 2015, Dominion convinced Virginia lawmakers to pass a bill that blocked the SCC from reviewing base electricity rates for the next seven years. (The utility had cited the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, saying it needed “rate stability” from Virginia in the face of expensive federal mandates. The Trump administration has since killed the environmental rule.)

The strategy has resulted in massive profits for Dominion while ratepayers’ bills soar. By law, utilities are entitled to earn about 10% profit on their assets and investments. Anything over that amount is considered “over-earnings,” money that could go back to customers as refunds. According to the SCC, Dominion made more than $500 million in excess earnings between 2017 and 2019.

The preliminary figures, released in a report in August, will be evaluated in a formal review next year. Dominion spokesman Rayhan Daudani said the company expects to use excess earnings for clean energy investments and assistance for people with unpaid bills during the pandemic. “The customer is getting benefit back from those dollars,” he said.

Years of excess earnings, however, have driven public anger. Today, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, Virginia households pay some of the most expensive electricity bills in the nation. Daudani said Dominion believes electricity rates are a better metric for comparison. The company’s rates are below the national average, he said, but Virginians use more electricity.

The utility’s residential power bills have jumped nearly 29% since 2007, largely due to new construction projects, according to an SCC report released in August.

“We have maintained reliable service, bolstered by our efforts to modernize the electric grid, and we have made record investments in clean energy,” Daudani said. “We are very proud of this record.”

Typically, state regulators would evaluate those projects to determine whether they were necessary. That’s how neighboring states oversee investor-owned utilities, which still earn millions in profit, said Joel Eisen, an energy and environmental law professor at the University of Richmond who has studied public utility regulation in America for 20 years.

But in Virginia, Dominion has routinely pressed the General Assembly to declare its projects “in the public interest,” language designed to force regulatory approval.

In 2007, lawmakers urged the commission to approve the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center, a $1.8 billion power plant in Southwest Virginia. They also awarded Dominion a bonus as an incentive to build the plant. Five years later when it started generating power, it was one of the last coal plants to open in the United States.

Today, it isn’t scheduled to operate more than 11% of the time. The plant, however, makes up the largest single generation charge on a customer bill: nearly $4 a month for the typical residential customer. A 2012 state attorney general’s office report showed customers are paying an extra $146 million to Dominion over the project’s lifetime for the bonus that lawmakers approved.

State regulators have questioned the need for some of Dominion’s most expensive projects. SCC officials said in a report in 2018 that the utility has regularly overstated electricity demand in Virginia. Daudani, the Dominion spokesman, said that as a result of that report the company changed the way it predicts demand.

Still, the utility has found ways to continue building and to keep its excess profits. In 2018, amid a brewing revolt over customer costs, Dominion supported a law to allow the company to invest much of the excess earnings in clean energy projects — instead of issuing refunds.

Eisen said he’s “unaware of any comparable provision elsewhere in the nation that allows a utility to take money that a commission would otherwise decide it has to give back to ratepayers and allow the utility to plow that into new projects.”

All of this led to a massive opposition effort. Beginning in 2018, a wealthy hedge fund investor, Michael Bills, offered financial support to any politician who refused to take campaign donations from Dominion. The response was overwhelming, with Bills shelling out $3 million to candidates and his political action committee, Clean Virginia.

Today, a third of state lawmakers have pledged not to take money from Dominion, its executives or lobbyists. Bills has supplanted the utility and every other person and corporation in Virginia as the state’s top political donor. He gave Northam $586,000 from 2013 to 2017, more than double Dominion’s contributions to the governor in the past decade.

Bills said in an interview that he has no investments that compete with Dominion. He wants the legislature to allow more competition for clean energy and empower state regulators to stop Dominion from keeping excess profits. “You can have clean energy and all the advantages of non-carbon producing energy without busting the bank,” Bills said, “and more importantly, busting the poor ratepayers’ backs.”

Dominion’s Friends in the State Senate

Democrats saw the Clean Economy Act as an opportunity to remake Virginia’s energy landscape and help lower power bills. Utilities would have to meet tougher energy efficiency targets and accept more solar and other renewable energy generated by producers other than Dominion.

Among the legislation’s primary authors was Virginia Advanced Energy Economy, a trade association that represents wind and solar developers, energy efficiency companies, and corporate energy buyers like Amazon and Facebook that want to reduce their carbon footprint.

Democrats in the House embraced the bill. But leaders in the Senate bristled. The upper house was ruled by Senate Majority Leader Dick Saslaw, a longtime Dominion ally from Fairfax County. Elected to the legislature in 1975, the 80-year-old lawmaker drives a purple Jaguar with the license plate “1” because he is Virginia’s senior state senator. A popular conservative radio talk show host calls him “the godfather.”

Dominion is Saslaw’s biggest political supporter. The utility’s PAC has given him $435,508 since 1996, nearly two times more than his second-largest donor, the Virginia Bankers Association, according to the nonprofit Virginia Public Access Project, which tracks money in state politics. And Dominion executives have given Saslaw an additional $48,000.

The utility is also the largest corporate donor to the Senate Democratic Caucus, giving nearly $400,000 in the past 20 years.

In 2019, as the anti-Dominion wave crested, Yasmine Taeb, a lawyer from Northern Virginia, challenged Saslaw in a primary, pledging to get excess Dominion earnings back to customers. She criticized what she called “‘an old Virginia way’ that still runs Richmond” and blasted Saslaw, who she said had “done Dominion’s bidding.” Saslaw has defended his record, saying the utility’s donations don’t influence his decisions. “I haven’t done any more than anybody else has” to help Dominion, he said in an interview.

With talk of a potential upset, Dominion stepped in. Five days before the election, the utility sent a letter to shareholders in his Senate district in the Washington suburbs touting his efforts on company projects.

Saslaw squeaked past Taeb by less than 3 points, his closest race in four decades. He spent about $1.4 million on the primary, seven times more than Taeb.

Saslaw told environmental leaders that to get any climate bill through the Senate, they’d need agreement from Dominion. In an interview for this story, he said that the state’s largest utility would be directly affected by the measure, so it needed to be a player in the discussions. “Your best legislation is when everybody involved reaches a compromise,” Saslaw said. “That’s the way the legislature works.”

After getting little out of past legislation backed by Dominion, environmentalists remained enthusiastic. “We were excited because for the first time we were working from our language,” said Harrison Wallace, then the Virginia director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network and one of the bill negotiators. “This was our bill, which we are now coming together to defend, and that was exciting.”

In Virginia, where the General Assembly usually convenes for an alternating 45 or 60 days each year, lobbyists have taken on an outsized role in policymaking.

Lawmakers file so many bills during the frantic sessions, rushing from hearing room to hearing room, that they often leave special interests to hammer out the details. So last January, at Saslaw’s direction, representatives of environmental groups and Dominion began a series of negotiation meetings. The lawmakers who sponsored the bill did not participate in the sessions.

A Conference Room With No View

At first, the environmental and clean energy negotiators tried to meet with Dominion representatives in the cramped state legislative building, even in the room designated for news conferences. But space was scarce.

Dominion offered a solution: The group could use one of the utility’s office towers just a few blocks from the Capitol. Environmentalists were reluctant; they wanted neutral ground and felt moving the talks would give their longtime foe an advantage. But, under pressure to reach an agreement, they relented.

Over the next five weeks, the group often decamped to a conference room that had one window looking out onto a brick wall. Negotiators would spend three- to five-hour chunks, sometimes all day, hashing out details of the legislation. Dominion occasionally bought meals from fast-casual restaurants like Chipotle for the group.

After years of Republican rule, the environmentalists were thrilled to be at the table. But now they faced the consummate political insider.

Bill Murray, Dominion’s top lobbyist and lead negotiator on the legislation, had 29 years of legislative experience, about half with Dominion. He had worked in the administrations of two former governors, Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, both now U.S. senators. After joining Dominion, Murray was part of the transition teams for the office’s most recent occupants, Terry McAuliffe and Northam.

Many lawmakers, especially those of the older generation, know and trust Murray because they’ve worked with him for years. He has personally given campaign money to more than 30 current lawmakers — a fifth of the General Assembly. Joining Murray at the table was Katharine Bond, a 21-year veteran of Dominion who was the lobbyist at the environmental groups’ press conference with lawmakers.

Murray gave advice to the environmentalists and told stories about how to get a bill passed in the legislature, said Wallace of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network. But he and Bond had a consistent message for the other negotiators: The provisions of the Clean Economy Act as presented were too costly.

The talks dragged on, and environmentalists believed that Dominion was using delay tactics. For instance, the utility initially agreed to annual benchmarks on energy efficiency designed to save customers money but later pared down the program, environmental negotiators said. Daudani, the Dominion spokesman, didn’t directly address the negotiations but noted that state regulators will set new efficiency targets after the program ends.

The change prompted a lobbyist with the Natural Resources Defense Council to leave the negotiations on Jan. 30.

By February, the talks were shaky. “Legislative negotiations are always complicated and miscommunication can happen, but this occurred too often to be pure coincidence and caused unwarranted delays,” said Harry Godfrey, the executive director of Virginia Advanced Energy Economy.

Murray responded in an interview that everything had to be checked “with the people who operate the grid.” To some in the room, it was as if the legislature had not changed hands.

“In the Public Interest”

The original Clean Economy Act called for offshore wind as part of a mix of clean energy but didn’t include language mandating that Dominion own it. The utility wanted to change that.

After years of investment in coal, natural gas and nuclear power, it had recently expanded into renewable energy. The utility won a federal lease for the area off the coast of Virginia Beach in 2013, as it considered building an offshore wind farm. Five years later, in 2018, it was pursuing a two-turbine test project. Just as it had done with its previous construction efforts, Dominion successfully pressed the legislature to declare the pilot project “in the public interest.” Saying the law tied its hands, the SCC approved the project but raised concerns.

The turbines would cost customers $300 million and generate 12 megawatts of electricity, enough to power only 3,000 homes with sustained winds. The cost of the wind energy was 26 times greater than purchasing it from the market and nearly 14 times greater than solar, the commission wrote in its order. Regulators said that customers would bear almost all of the risk if costs went up or the project flopped.

Now, in early 2020, with the test project still under construction, Dominion pushed to go bigger. It wanted to build a $7.8 billion expansion, which would make its offshore wind operation the largest in the nation. And it saw the Virginia legislature as the vehicle to make it happen.

Offshore wind is largely a new frontier in America. During the legislative session, there was only one offshore wind farm in the United States, made up of five turbines off the coast of Rhode Island. There are 18 projects in the planning stages in other states, according to the American Wind Energy Association. But Virginia Democrats, many of whom campaigned on promises to combat climate change and protect the environment, backed Dominion’s plan.

While environmentalists and Dominion negotiated in the utility’s office tower, the Democratic sponsors of the Clean Economy Act, Del. Rip Sullivan of Fairfax County, and Sen. Jennifer McClellan of Richmond, added language that declared the wind farm “in the public interest.”

Another addition to the bill went further. It said the SCC should find certain costs to be “reasonably and prudently incurred.”

The provision meant legislators were directing state regulators to approve a future request from Dominion to recover billions from customers for its offshore wind plan.

While the SCC still makes the final decisions, the “reasonable and prudent” language makes the commission’s hearing more of a formality. The Virginia attorney general’s office warned lawmakers early in the session that the wording takes away a key ratepayer protection.

Such language is not the norm elsewhere, said James Van Nostrand, a utility law professor and director of the Center for Energy and Sustainable Development at West Virginia University who spent 22 years representing investor-owned utilities. Typically, he said, a public utility commission would determine whether a proposed project should move forward. The regulated utility has the burden of proof to show regulators that its proposed costs are reasonable and prudent.

The Clean Economy Act removes that burden, he said, calling it “a big advantage for the utility to have this… The more the legislature weighs in, the more you see what Dominion can do just by its influence over the legislature,” Van Nostrand said in a recent interview. Lawmakers are removing authority “from an agency that has the expertise and has the proceedings that invite the level of rigor and scrutiny that’s going to test that number.”

The lawmakers who sponsored the bill said they largely left the details to Dominion and the environmental groups. “Other than just generally focusing on ‘What can we do to expand wind,’ I was not involved in the weeds of the language negotiations,” said McClellan, who sponsored the legislation with Sullivan. “Rip and I basically told all of the stakeholders: ‘Negotiate this bill. When you can’t reach agreement, come to us and we’ll be the tiebreaker.’”

Sullivan said in interviews that the language came from “the ongoing collaborative process between lots of stakeholders. And I think I’d be misdescribing the process if I told you that one particular person or one particular entity asked for that specific language. It became part of the ongoing discussions.”

But key environmental negotiators — including Wallace of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, Will Cleveland of the Southern Environmental Law Center and Mike Town of the Virginia League of Conservation Voters — said they didn’t write the language or help write it.

Dominion’s Murray and Bond said they didn’t know who wrote it; asked if Dominion’s lawyer wrote it, Murray said the utility’s legal representatives were “involved in discussions about it,” but the company declined to provide more detail.

“Is it not the case that the reason we have not had a rate review … is because of two bills that you all helped draft and asked for?” he asked during a House subcommittee hearing. The bill easily passed the House. Then, it went to the Senate Commerce and Labor Committee. At the helm: Saslaw, the state’s most-senior senator.

The sponsors made their case and a long line of supporters formed to speak. “This is about protecting the consumer, protecting the ratepayer,” said Del. Jay Jones, D-Norfolk. “That money belongs in the pockets of the people of Virginia.”

But Dominion lobbyists told lawmakers the bill would undercut Dominion’s ability to do clean energy projects, a claim refuted by the SCC. Browder, speaking softly and without naming Dominion, told senators, “I believe that there may be some attempt at confusion on the issues here.”

He reminded them of times Dominion made claims that didn’t pan out, like in 2014 when lawmakers passed a bill allowing Dominion to charge customers for research on a nuclear reactor. The utility had argued it needed the funds to keep the project moving. Dominion charged customers $320 million for the work but later paused development of the reactor.

Others on the panel defended the utility. “There are 26 to 29 states with higher rates than Dominion, so are they ripping off their customers too?” Saslaw asked one speaker; two speakers then told him rates are only part of what Dominion customers see on their bills. Dominion’s base rates make up about 60% of the average residential power bill, with additional charges for construction projects and fuel costs making up the rest.

The Senate Republican leader, Tommy Norment, accused “environmental groups and lower-income groups” of having “done their absolute unequivocal best to bend Dominion over in every way imaginable.” The rate bill died in the Senate committee, 8-7. Six Democrats, including Saslaw, were joined by two Republicans in killing the measure.

With a Little Help From the Governor’s Office

For much of the session, environmental groups and Dominion were at an impasse over the Clean Economy Act. And with time running short, the Northam administration stepped in to mediate. The governor, who had called for ambitious clean energy goals, supported Dominion’s offshore wind plan. He also had deep ties to the utility. Dominion has contributed $291,000 to Northam’s political campaigns and committees throughout his career. Northam also had tapped some of the utility’s top lobbyists — including Murray — to help his transition team in 2017 and later hired Dominion’s director of strategic communications as his chief communications officer.

Angela Navarro, Northam’s deputy commerce secretary, led talks between Dominion and the environmental groups.

Before entering state government, she was a lawyer for the Southern Environmental Law Center. Both sides saw her as a credible broker. Emails obtained through the Virginia Freedom of Information Act show Navarro taking the lead in making changes to the Clean Economy Act based on the negotiations.

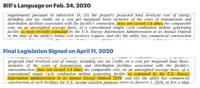

One of the sticking points was cost: The amount lawmakers would order regulators to approve for the offshore wind project was obscured in the bill by a complicated equation. One part called for multiplying the energy cost of a certain type of natural gas plant by 1.6. Negotiators agreed to reduce 1.6 to 1.4, thereby cutting the projected cost.

Another part of the equation specified that the average energy cost of that gas plant should be the cost most recently estimated by a federal agency.

On Jan. 29, the most recent federal estimates were published, showing a 25% drop from 2019. Under the bill’s language, that meant the amount the legislature was telling regulators to allow Dominion to charge its customers fell, to $7.3 billion.

But on March 4, the day before lawmakers would introduce a new version for a final debate, Navarro made a critical alteration to the legislation.

Records show she changed “most recently” to “2019,” a tweak backed by Dominion that immediately boosted the acceptable price tag of the offshore wind project. The increase was roughly $2.5 billion, an analysis by the SCC would later show.

Navarro said in a July interview she had no records from anyone asking her to make that change. She said the group negotiated the language. “I think we discussed it amongst all of the stakeholders,” Navarro said.

But five of the main environmental and trade association members who participated in discussions told the Times-Dispatch and ProPublica they did not ask for the alteration and weren’t aware of it at the time. “We definitely did not ask for that change,” said Town, of the League of Conservation Voters.

Documents obtained through a FOIA request show that the language change was, in fact, a priority for Dominion. And phone records reveal that Navarro spoke to the utility’s representatives on March 4 just before and after emailing negotiators the tweaked legislation. One of those representatives did not return phone calls seeking comment and the other said she did not remember the nature of the conversation.

The next morning, a lawyer for Dominion emailed Navarro requesting several changes to the bill, records show. A state bill drafter had added “2019” to the cost formula, as Navarro directed, but did not cut “most recently.” The Dominion lawyer told Navarro to strike “most recently” and listed that request among “policy choices/more than typos.”

Dominion’s legal team also wanted Navarro to insert language into the bill that would allow Dominion to charge its Virginia customers extra if North Carolina regulators wouldn’t let the utility pass the Clean Economy Act charges along to Dominion’s 123,000 customers there. That language had been removed inadvertently, so Navarro approved putting it back into the legislation.

Navarro declined to comment about her phone records, her emails and the statements from environmental negotiators that they had not been involved in the key change that benefited Dominion.

Clark Mercer, the governor’s chief of staff, said in a statement for this story that Navarro was not aware of any new federal data that would have changed the cost in the bill until after the bill passed, and he wrote that she believed the change was “consensus language” from stakeholders.

Navarro left her job in the governor’s office on Sept. 4. Northam’s press secretary said Navarro had been planning to leave for several months.

Clean Economy Act supporters note that Dominion will be required to take competitive bids for most of the work to build the offshore wind farm, which it said would lower costs. But under the bill, Dominion can recover at least $9.8 billion in costs — more than $2 billion above its latest estimate, the SCC later said in an analysis.

A Historic Law, a Risky Bet

Lawmakers in the House debated the new version of the Clean Economy Act on March 5. No one brought up the change in the cost equation or the resulting dollar amount.

McClellan, the Senate sponsor, told the Times-Dispatch and ProPublica she was unaware of the alteration until the news organizations asked her about it, months after the bill passed. Sullivan, the House sponsor, said he was aware of the change but not the resulting dollar amount.

That day, Sullivan described the Clean Economy Act as “transformative and historic” and said it would help the coastal Virginia region become a national hub for offshore wind manufacturing. Other states “are vying to become that hub,” he said on the House floor, “and Virginia needs to act now.”

But a few Democrats spoke against the bill, casting it as a giveaway to Dominion. Del. Lee Carter, a Democratic socialist from Manassas, told his colleagues that they had been manipulated. “Dominion Energy’s addiction is to its monopoly power and to ratepayer money, and they have adapted to Democratic control over the General Assembly,” he said. “In previous years, they’ve gotten their ratepayer money through fossil fuel projects because that is what they could get through a Republican-held General Assembly. Now they have adapted and they’re doing their price gouging on renewable energy projects. They are, in my opinion, taking advantage of this new majority’s desire to do something for the environment and they are using that as a way to gouge the citizens of this commonwealth.”

Rasoul, the Dominion critic from Roanoke, introduced amendments to reduce the cost of offshore wind development, but Sullivan labeled them a “poison pill.” The majority killed them.

The Clean Economy Act passed the House, 51-45, on March 5, and passed the Senate, 22-17, the next day. One Republican in each chamber joined Democrats. Northam signed the legislation in April.

The environmental negotiators say they are happy with the progressive policies in the new law. Its mandate that utilities generate all electricity without fossil fuels by 2050 is the first of its kind in the South.

The law requires the SCC to consider the social costs of carbon emissions for new utility projects, which environmentalists say will help the state fight climate change. “It will be very hard for Dominion to get approval to build any gas of any size,” said Cleveland, who helped write the original Clean Economy Act.

The law also shrinks Dominon’s energy monopoly a bit, allowing private parties to own 35% of new large solar projects. Previous law capped that amount at 25%. Environmental negotiators wanted a 50-50 split.

Other environmentalists, however, said the bill moves too slowly toward a transition to renewable energy. On energy efficiency, the language in the law was watered down to the point that the utility can nearly meet the mandate through programs it already planned under a previous law, according to a company filing.

Will Reisinger, a former assistant attorney general who practices with Richmond clean energy firm Reisinger Gooch, said the bill is good for Dominion because it allows the company to make a lot of money. And the legislature missed an opportunity to pair that with fair electricity rates. “We have to pay attention to costs,” he said. “If we do the clean energy transition in a really expensive, inefficient manner, it’s going to impose unreasonable, unbearable costs on consumers and businesses and I just don’t think it’s going to work.”

But from Wall Street, Virginia took away risk for investors, which is important, said Shar Pourreza, managing director for North American power and utilities at New York investment firm Guggenheim Partners. In other states, the risk of developing offshore wind is on the utility, he said.

For Dominion, the law has taken on even more significance.

Four months after the session ended, on July 5, its parent company announced it was selling its gas assets and canceling plans to build the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, an $8 billion project to carry natural gas from West Virginia. Dominion said the federally regulated project collapsed, in part, because of legal challenges from environmentalists.

Dominion Executive Chair Tom Farrell said in a news release that the company would instead focus on something else: A clean energy profile in “its premier state-regulated, sustainability-focused utilities.”